A Rapid Review of the Use of Appropriate Technology in Global Health

Article information

Abstract

The need for appropriate technology in global health has expanded dramatically as the gap between industrialized and developing countries continues to expand. However, there is no collective knowledge of appropriate technology in global health. Thus, this study intends to provide light on the latest developments in the field of appropriate technology in global health and to speculate on future directions. A rapid review, or simplified technique, was used to systematically identify and summarize emerging papers. The search technique used the keywords “global health” and “appropriate technology.” The total number of papers collected from PubMed and Scopus was 427, and 19 articles were thoroughly reviewed for the result section following the research. The study's conclusions included the following: 1) an assessment of appropriate technology adopted in developing countries; and 2) strategies for implementing appropriate technologies in global health. Additionally, we drew lessons and identified problems to serve as a useful guide for future research and development in appropriate technology. This review uncovered a small but valuable level of information about acceptable technology in global health.

Introduction

Appropriate technology is defined as any object, idea, process, or practice that fulfills human needs under consideration of the community’s political, cultural, environmental, and economic conditions. Economist Dr. Ernest Friedrich Schumacher, who first coined the term “appropriate technology,” argued that appropriate technology must be small scaled, locally controlled, inexpensive, ecologically sound, energy efficient, labor-intensive, and compatible with human needs (Schumacher n.d.). Such features of appropriate technology make appropriate technology a good foundational tool for less developed countries to fulfill the basic needs of their people who have been largely left out from the modern industrial process.

The need of appropriate technology in global health has significantly increased following the ever-growing gap in economic development between developed and developing countries. The economic gap has been a major limiting factor in transferring developed countries’ health related services and technology to developing countries. As a result, appropriate technology has played an effective mechanism that transformed modern technology into what can be most ideally accepted by those w ho use it.

The WHO Basic Radiology System (BRS) in 1975 is an example of appropriate technology in global health. BRS is a “simplified version of a standard radiographic unit” that can perform routine radiographic examinations in regions deprived of radio diagnostic service for economic and geographic reasons (World Health Organization 1994). The WHO BRS demonstrated high quality images and administrative advantages including safety, energy efficiency, and ease of use. By 1991 the WHO BRS was known to report the highest number of radiographs awarded and met the common needs of the majority in cases such as fracture, pregnancy, chest diseases, parasites, and abdominal pain (ibid).

Current uses of appropriate technology in global health are countless. Appropriate technology is used in laboratory medicine technology, allowing rapid and easy-to-access diagnostic tests to infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Its use is also found in gene technology, starting from early detection and prevention of infectious disease and hereditary diseases to application in food production. It also enhanced the delivery system of pharmaceuticals and is widely used in environmental health to clean wastewater and develop safe housing designs.

However, appropriate technology still lays concerns before it gaps knowledge and application. Common limitations of application of appropriate technology include lack of access to databases or other sources of information, lack of funding, lack of commitment and political support, weak national health care system, poorly equipped hospitals, and lack of national expertise. As such, it is critical for global and national health institutions to collaborate with local organizations and donor agencies to ensure that they accurately review limitations of existing systems and develop more rational mechanisms that are effective according to the community’s needs and priorities. By categorizing and summarizing the evidence, this rapid review aimed to provide a present status of existing research of appropriate technology in global health.

Method

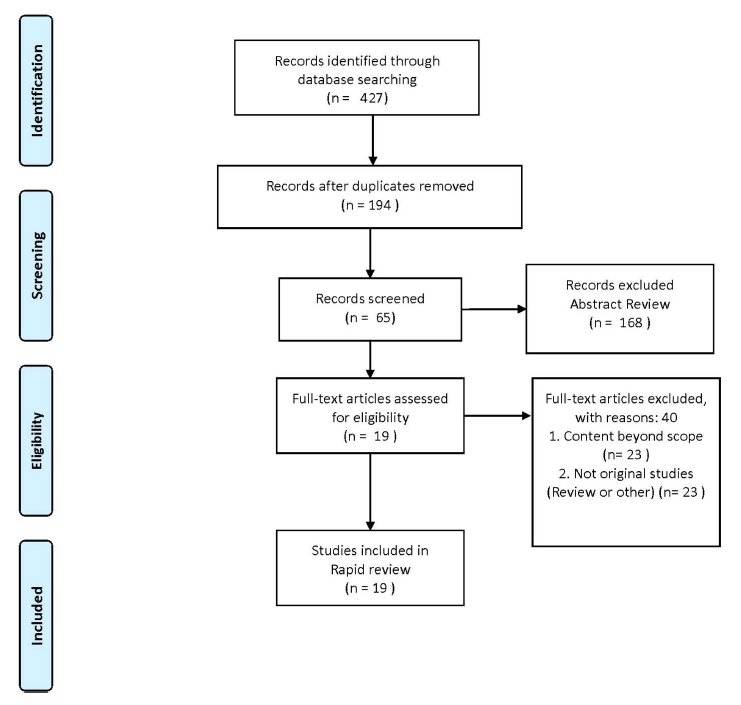

Rapid review is a form of systematic review in which current studies are carefully examined to see if they match the researcher's point of view or a specific research issue. In this regard, rapid review is useful for knowledge synthesis. We conducted a rapid review based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist in order to examine the current status and application cases of health-related appropriate technologies globally and to present the factors that influence the introduction of such appropriate technologies.

1. Eligibility criteria

Appropriate Technology is described as “any object, idea, process, or practice that fulfills human needs while taking into account the community's political, cultural, environmental, and economic conditions,” as previously said. The medical system or systemic improvement can also be offered as a form of healthrelated appropriate technology. In light of the current pandemic crisis and the broad availability of mobile devices, it presents the possibility of expanding appropriate technology offered in a non-face-to-face public approach as a means of medical system development. This paper developed the following screening criteria based on this viewpoint on appropriate technology. Records are widely collected through PubMed and Scopus using the phrases “global health” AND “appropriate technology” and verified for eligibility through the following steps:

1. A record is excluded and categorized as ‘Content beyond scope' if it merely provides a simple technical introduction, animal-related intervention, or consequence that is assessed to be unrelated to health.

2. If a record isn't regarded an original article, such as a review or commentary, we opted to remove it and label it as “Not original study.”

Papers that presented criteria in the process of introducing appropriate technology were also included as a result of researcher discussion.

2. Study selection

The following process was used to choose the studies. A total of 427 papers were uploaded in the Rayyan system (http://rayyan.qcri.org), a free web-based research tool for systematic review. Then it was uploaded to the Mendeley program for review. 194 papers were deleted from the screening process because they were duplicates. The first round of screening was done using abstract analysis, and 168 items were eliminated. A secondary screening was carried out for more thorough verification. 23 records were identified as having content that was outside the scope of the project and were removed. A total of 23 entries were categorized as a non-original study, displaying Review or Commentary characteristics. In total, 42 papers were rejected based on the aforementioned criteria. The remaining 19 records were chosen as research articles, and mutual verification was carried out through talks among scholars.

Results

1. Characteristics of the selected studies

The features of the 19 studies considered in the review are summarized in Table 1. The research location is one of the elements extracted. The research was conducted in low- and middle-income countries on the African and Asian continents. Nine research (9/19, 47.3%) have been completed in the African region (Dunmade, 2002; Liang et al., 2018; Morse et al., 2020; Mulokozi et al., 2001; Parham et al., 2010; Ritenbaugh et al., 1989; Sanborn and Toure, 1984; Sesan, 2012); and five studies (5/19, 26.3%) have been completed in the Asian region (Khodadadeh et al., 2001; Labbé et al., 2001; Monk, Hall, and Hussain, 1984; Nelson, Sutanto, and Suradana, 1999; Parashari et al., 2000). Another feature that has been retrieved is the research design. This review categorized the selected papers on appropriate technology and global health according to their research designs. The research designs used in selected studies include narrative research (6/19, 31.6%) (Dunmade, 2002; Feachem, 1980; Free, 1992; Monk, Hall, and Hussain, 1984; Nabarro and Chinnock, 1988; Ong, 1991), clinical trial research (6/19, 31.6%) (Jeronimo et al., 2014; Labbé et al., 2001; Mulokozi et al., 2001; Nelson, Sutanto, and Suradana, 1999; Parashari et al., 2000; Ritenbaugh et al., 1989; Sanborn and Toure, 1984), case studies (2/19, 10.5%) (Parham et al., 2010), randomized control trial research (1/19, 5.3%) (Khodadadeh et al., 2001), qualitative research (1/19, 5.3%) (Sesan, 2012), cross-sectional research (1/19, 5.3%) (Liang et al., 2018), and transdisciplinary research (1/19, 5.3%) (Morse et al., 2020). Additionally, the selected studies' objectives and outcomes were obtained. The studies that were chosen to highlight the following outcomes: performance, usability, and needs. Ten studies illustrated the performance of appropriate technology launched there in research (10/19, 52.6) (Jeronimo et al., 2014; Khodadadeh et al., 2001; Labbé et al., 2001; Liang et al., 2018; Nabarro and Chinnock, 1988; Nelson, Sutanto, and Suradana, 1999; Parashari et al., 2000; Parham et al., 2010; Ritenbaugh et al., 1989; Sanborn and Toure, 1984; Sesan, 2012), four studies included usability as a research objective and measure (4/19, 21.1%) (Dunmade, 2002; Monk, Hall, and Hussain, 1984; Morse et al., 2020; Ong, 1991), two studies joint performance and usability (2/19, 10.5%) (Liang et al., 2018; Mulokozi et al., 2001), and two studies indicated the need for appropriate technology (2/19, 10.5%) (Free, 1992; Leggat, 1997).

2. Evaluation of appropriate technologies implemented in developing countries

Fifteen studies examined appropriate technologies in developing countries, and we analyzed the evaluation results to identify the strengths, limitations, and recommendations for appropriate technology use. Table 2 summarizes the assessment for each study. These findings were mainly positive in their evaluation of appropriate technology use in low-resource settings. The majority of studies evaluated appropriate technologies as easy to use (Khodadadeh et al., 2001; Labbé et al., 2001; Mulokozi et al., 2001; Nelson, Sutanto, and Suradana, 1999). Numerous studies have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of appropriate technologies (Leggat, 1997; Parashari et al., 2000; Parham et al., 2010). According to certain research, appropriate technology can help decrease health risks by supplying drinkable water and reducing smoke generated during cooking (Morse et al., 2020; Sesan, 2012). Furthermore, studies have indicated a beneficial influence on women's productivity and efficiency (Mulokozi et al., 2001), improvements in patient assessment (Nabarro and Chinnock, 1988; Ritenbaugh et al., 1989), speed of use (Sanborn and Toure, 1984), and maximizing of local labor and resources (Monk, Hall, and Hussain, 1984).

This rapid review also explored limitations. Some studies mentioned a deficiency of necessary functions (Khodadadeh et al., 2001; Parham et al., 2010). Several studies also cited disputes amongst community residents, such as artisans demanding high fees for their services (Mulokozi et al., 2001), and competition between traditional birth attendants and nurses over the use of appropriate technology (Ritenbaugh et al., 1989). Certain research indicated low community participation in implementing appropriate technologies as their limitation (Morse et al., 2020; Nabarro and Chinnock, 1988). As per with one study, their constraint is the inability to discard huge disposables of appropriate technology (Nelson, Sutanto, and Suradana, 1999), while another study discovered a lack of data portability between hospitals (Liang et al., 2018). Furthermore, one study noted that appropriate technology was difficult to learn at first use (Sesan, 2012).

Notable recommendations include the use of community leadership (Morse et al., 2020), user training (Jeronimo et al., 2014; Liang et al., 2018), sequential piloting of appropriate technology (Liang et al., 2018), an evaluation method at each stage of implementation (Parham et al., 2010; Sesan, 2012), and additional appropriate technology that would enhance the integration of existing technology (Leggat, 1997; Parashari et al., 2000).

2. Implementation strategies for appropriate technologies in global health

Table 3 shows the strategies for implementing appropriate technology in global health. The assessment method and factors influencing prototype development and implementation (program environment factors, implementer related factors, recipient related factors, contextual factors) (Morse et al., 2020), adoptability (Dunmade, 2002), design (identify technology), and specifications (identify need) (Free, 1992) are all evaluated as input indicators. Promotional approaches (codesigned community-based prototype, message for technical use of treatment system, promoting use through behavior modification strategies) and process indicators (Morse et al., 2020). Technical, environmental, economic, and socio-political sustainability were identified as essential indicators in the appropriate technology implementation strategies for output criteria (Dunmade, 2002). Ong additionally identified components of work factors in human-machine interactions as crucial implementation indicators (Ong, 1991).

Conclusion

Appropriate technology in global health is a crucial intervention enhancing health in developing countries. In this rapid review, we identified 19 studies to systematically organize the existing appropriate technologies, their evaluation results, and implementation strategies.

In general, research have demonstrated the development of appropriate technologies of use in the field of global health. Additionally, numerous appropriate technologies have been implemented throughout the last four decades and have remained mostly concentrated in a few countries. Most of the research has focused on the deployment and performance of distributed technology in low-resource contexts. According to the analyzed research, the intended users were primarily community residents and health care professionals. However, the examined studies do not include an assessment of longterm health outcomes and they are primarily concerned with short-term outcomes. Furthermore, several implementation strategy components were discovered that might be used to the evaluation criteria.

1. Study Limitation

Our study may be limited by publication bias. This study did not include non-peer-reviewed articles, such as grey literature or program reports, and articles written in language other than English.

2. Critical components of implementing an appropriate technology in the Global health arena

1) Community participation

Numerous studies in this rapid review have established the significant importance of engaging the community in the application of appropriate technology in low-resource situations. The Alma Ata Declaration of 1978, which established the community as a critical component of primary health care planning, organization, operation, and control, elevated community engagement to a new level (WHO, 1978). Community involvement has emerged as a global health aim in recent years, with the establishment of the new Sustainable Development Goals. Integrated, people-centered health care is crucial for reaching the SDGs' goal of universal health coverage, and accomplishing this goal requires participatory approaches (Marston et al., 2016). Apart from enhancing the efficiency of health initiatives through community participation, it is argued that effectively involving communities improves social capital, leading to increased community empowerment and, eventually, improved health status and reduced health inequities (Morgan, 2001). In this manner, including the community while using appropriate technology to promote health in low-resource settings makes the technology more sustainable.

2) Systems approach

Our findings emphasize the importance of a systems approach to disseminating appropriate technology in global health as shown in Figure 1. Delivering health related appropriate technology in lowresource regions is highly complex, as it requires the convergence of multiple disciplines. Integrative systems-based methodologies such as systems approach are increasingly attracting attention for their ability to promote the transdisciplinary collaboration (Mercure et al., 2015). One of main parts of systems approach is systems thinking which defined as “an integrated approach to grasping the dynamic linkages between complex economic, environmental, and social systems and assessing the potential consequences of change.” (Fiksel et al., 2014) Systems thinking captures how to intervene to improve population’s health. Systems thinking to selecting appropriate technology necessitates a scientific understanding of system complexity and an understanding for technology's role in health improvement. As a whole, our understanding of how to adopt appropriate technologies to improve health outcomes will be strengthened by a systems approach.

3) Long term health outcome

Several studies have mentioned short term health outcomes such as improvement of immediate health services, advancement of specificity and sensitivity, and performance of health care technologies (Jeronimo et al., 2014; Labbé et al., 2001; Liang et al., 2018). However, there is a dearth of information on the long-term health outcomes related with appropriate technology intervention. The professional developers must have a firm grasp on the effect that healthy interventions can have on one’s prevailing and long-term health. Such studies are necessary to expand the range of possible health outcomes associated with clinical outcomes while including patient satisfaction as an endpoint.

3. Future direction

Various adaptable and low-marginal-cost digital interventions are being proposed as appropriate technologies these days. Digital technologies (apps, wearables, EHRs, and mHealth) have the potential to create a technology-enabled health system in which care exchanges occur outside of hospital settings and community individuals are encouraged to self-manage their health and illness (Greaves et al., 2019). Prior to developing and implementing digital health systems in low-resource settings, it is critical to determine whether an organization, institution, as well as a region or country is prepared to adopt new technology and processes. It is essential to understand the beneficial and negative perceptions of digital health systems among healthcare practitioners, engineers, patients, community residents, and program administrators. Therefore, measuring preparedness is one of the first elements in building a digital health plan for future direction.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.